Medical devices have been implanted in human bodies for decades, starting with the first pacemaker implanted in 1958. In fact, it is estimated that 10% of the US population has had an implanted medical device1. The number of people with implanted materials is expected to increase dramatically over the next decades as implantation technologies advance and the devices shrink2, leading to a 7% projected annual increase in utilization3.

While devices such as pacemakers have been successfully implanted in the body for over 70 years4, the more recent application of nano- and micro-scale technologies face multiple challenges, including:

- low reliability,

- migration from the target site,

- poor durability, and

- lack of biocompatibility.

In the following article, we’ll examine Biocompatibility through the lense of therapy development and discuss:

- An Overview of Biocompatibility (and the impact of non-biocompatible material on therapies).

- The Foreign Body Response to implanted material.

- Acute Inflammation (and how the body initially tries to destroy implanted material).

- Chronic Inflammation (and the longer-term impact of the foreign material)

Biocompatibility

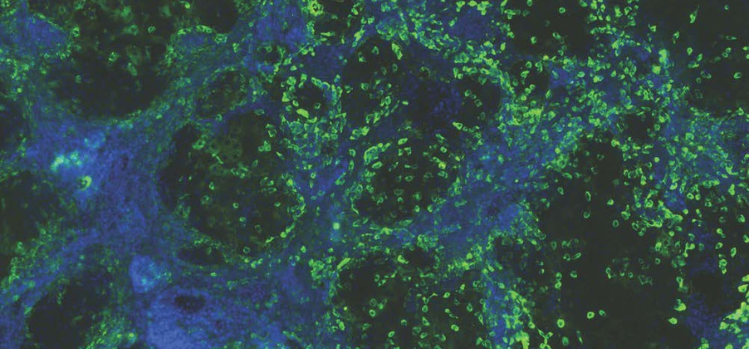

Any time a foreign object is inserted into the body, the body responds to try to remove it, typically through phagocytosis or by surrounding it with a thick layer of collagen to wall the object off from the rest of the body. Thus, the term “biocompatibility” relates to the degree to which the body will attempt to remove or limit the foreign object. When something is described as biocompatible, it really means that the body has a minimal response to the implanted or injected material.

In the best cases, the area around an implanted object responds with acute inflammation normally associated with wound healing, because the physical act of implanting a foreign material causes a local wound5.

However, shortly afterwards, the inflammation should subside with limited scarring around the foreign material, leading to healing of the surrounding tissue. In this example, the implanted material would be defined as biocompatible, because it only elicited a minimal short-lived response that quickly resolved.

When a material lacks biocompatibility, it induces an adverse immune response that can be characterized by localized or systemic inflammation, fibrotic overgrowth, tissue destruction and eventually rejection of the material. The process by which the body rejects a material is called a “foreign body response”. This is particularly important when the implanted material is small in size such as when cells are encapsulated in hydrogels. When cells are covered in a non-biocompatible material, the result is loss of the cell function and death of the transplanted cells.

Read the rest of the article and learn more about:

- The Foreign Body Response to implanted material.

- Acute Inflammation (and how the body initially tries to destroy implanted material).

- Chronic Inflammation (and the longer-term impact of the foreign material).

Download the full Biocompatibility article here:

Resources

1. G. Jiang, D. Zhou, Technology advances and challenges in hermetic packaging for implantable medical devices, in: D. Zhou, E. Greenbaum (Eds.), Implantable neural prostheses 2: techniques and engineering approaches, Springer, Berlin, 2010, pp. 28-61.

2. M. Major, V. Wong, E. Nelson, M. Langaker, G. Gurtner, The foreign body response at the interface of surgery and bioengineering, Plastic and Reconstruct Surg 135 (2015) 1489-1498.

3. E. Meng, R. Sheybani, Insight: implantable medical devices, Lab Chip 14 (2014) 3233-3240.

4. Y.-H. Joung, Development of implantable medical devices: from an engineering perspective, Int. Neurourol J 17(3) (2013) 98-106.

5. D. Gurevich, K. French, J. Collin, S. Cross, P. Martin, Live imaging the foreign body response in zebrafish reveals how dampening inflammation reduces fibrosis, J Cell Sci 133 (2019) jcs236075.